Everyone’s Responsible for our Morning Coffee

For the 12.4 million smallholder coffee farmer families across the globe, climate change is already a real threat to their economic existence. Nevertheless, adapted cultivation techniques and access to new technologies could make them supporters in the fight to achieve the Paris climate goals, as experts agreed in an online round-table talk organized by the initiative for coffee&climate (c&c) marking the kick-off of the third phase of c&c.

Despite growing awareness and more action on the ground, climate change has become a major challenge to coffee production worldwide. Already today, in 2021, poverty in rural coffee areas has increased, farmland has been abandoned as unprofitable, and entire coffee areas are at risk of being completely lost due to degrading climate conditions. In an online round-table discussion to which more than 300 guests registered, Veronica Rossi (Sustainability Manager at Lavazza), Cecilia Brumér (a Program Specialist at the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency Sida, Stefan Ruge (Program Manager at Hanns R. Neumann Stiftung (HRNS) in Hamburg) and Dulce Posadas (a smallholder coffee farmer in Honduras) discussed the main challenges and constructive solution strategies for climate-resilient coffee production.

Serious Impact

As a second-generation coffee farmer, Dulce Posadas has first-hand knowledge of climate change and knows its problems all too well. “Climate change was something not talked about in past generations, until we experienced the impacts in our own community,” she remembers. Heat, drought, pests, diseases and late crops ‒ these effects of climate change, which her family at first did not know how to manage, all had a serious impact on the production as well as the quality of their coffee.

Brumér can verify the impact of these factors with scientific evidence. She claims that, according to the World Economic Forum, climate change was rated the top global risk in terms of likelihood and impact, putting both the planet and humanity in danger. “Climate change affects us all, but smallholder farming families are among the hardest hit because they depend on natural resources in a direct way,” she states.

“The main challenge is climate change”

Rossi agrees. “We have to focus on the main challenge, which is climate change,” she says. Speaking from her experience with Lavazza, she emphasizes that it is vital for big companies to realize this when they are “dealing with a commodity like coffee, which is so much impacted by climate change.”

The increasing climatic threat to coffee production and smallholder families, both Rossi and Brumér agree, has been underrated or ignored far too long by different actors in the coffee sector. Now, the risks must be assessed and action taken in a more “coordinated” and “focused” way.

To better the situation, Rossi is convinced that “farmers need to be at the center” of the new strategies. “They need to be with us in the solution, definition and implementation because they are the ones in the field.”

Third phase of coffee&climate has started

Recently, coffee&climate (c&c) launched its third program phase, which promotes a more holistic approach to the challenges of climate change and centers around the farmers and their families, as Rossi is urging. Regarding the aim of the new solution strategies, as Ruge explains, “productionsystems should not only be resilient to climate change, but also improve the overall situation of the livelihoods of farming families.” It does not help “just to focus on the economy or one single component.” Therefore, the third program phase involves family farming, gender equality, carbon offsetting and the dynamic integration of the younger generation as well as turning increasingly to digital solutions.

The third phase of c&c is based on the idea of sector wide pre-competitive partnership driven by the shareholders of International Coffee Partners (ICP): Delta Cafés of Portugal, Franck of Croatia, Joh. Johannson of Norway, Lavazza of Italy, Löfbergs of Sweden, Neumann Gruppe of Germany, Paulig of Finland and Tchibo of Germany together with the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency Sida.

Carbon offsetting

In the future, smallholder production systems could become a cogent force in reducing carbon emissions. “We have more than 12 million smallholder families around the world producing coffee, protecting local forest areas and pursuing good soil management ‒ this could be part of the solution to meeting the Paris Agreement,” Ruge explains. To halt climate change, it is important to limit global warming to no more than two degrees, as agreed at the Paris Climate Change Conference in 2015. Therefore, c&c plans to evaluate a framework of carbon accounting. “We believe that farmers should receive a financial incentive for maintaining good soil and local forests,” Ruge states. This would benefit smallholder families by providing an additional source of income while simultaneously meeting the demands of the coffee industry for the production of commodities in a carbon-neutral manner. Ruge’s credo: “The price of coffee has to reflect the real price of production with all the social and environmental aspects incorporated.”

Family Business

“Strong climate action needs a strong family,” Ruge explains with regard to c&c’s goal for its third phase, continuing that, since climate change increasingly and disproportionately affects women, the program “needs a strong gender component.” Brumér endorses this idea, stating that involving “all the family members and different generations” and focusing on gender equality “is key for development.” Dulce’s familiy is one of the finest examples for this. Together with her brother, mother, father and many uncles they are cultivating coffee as a family. Being part of the younger generation, Dulce sees it as her duty to teach the older generation to adapt the production process on the farm to the fast climatic changes. With her help, her parents have become aware of the challenges and together they have comitted to work with c&c to improve the conditions of coffee farming in their region.

Digital Solutions

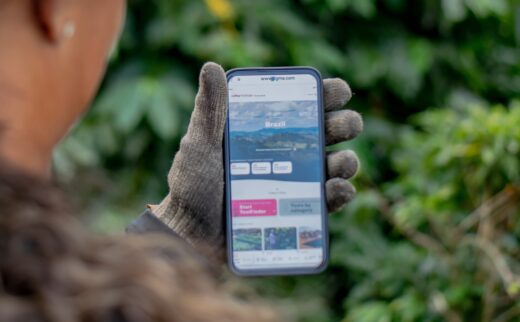

One aspect that Veronica Rossi finds increasingly important is access to technology and digital solutions. “It is costly, it is complicated, but it is the future,” she says. Ruge affirms that c&c has already invested in this area and will continue to focus on digital problem-solving in the third phase of the program. “We are assessing existing digital solutions and frequently used apps and platforms in the program regions to evaluate how to make best use of them for training activities and decision-making processes for farming families.” Thus, “agriculture can be made attractive for the next generation,” and knowledge about climate adaptation strategies and practices can be shared via online platforms, thereby becoming a common good.

Climate change is everyone’s responsibility

If the industry wants to maintain plentiful coffee harvests, why don’t they take sole responsibility for its climate-resilient production? Rossi replies that, in her opinion, “this is a systemic emergency where everybody should play their own part.”

Brumér agrees, pointing to the importance of long-term commitments and close cooperation between private and public institutions. “There is no way that the combined official development money in the world will help to achieve the ambitious goals that we have set in 2015,” she states within the framework of Sida’s already established collaboration with c&c. “Therefore the private sector is key.” All actors need to work together to achieve the development of climate-resilient coffee production, she believes.

“We are all responsible for our morning coffee,” Rossi adds. And, as Ruge points out, as a strong, dedicated, pre-competitive partnership, c&c is offering a wide range of opportunities for private and public collaborators, NGOs and academia. Join the network!

Join the network!

The initiative for coffee&climate is based on the power of pre-competitive partnerships. We are unified by the wish to build a climate-smart coffee sector not by talking, but by acting. As the challenges of climate change for coffee production are too big to be tackled alone, c&c is the ideal solution for the coffee sector to respond together in a practical way that cannot be found in other setups.

Dulce Posadas: “We’re all passionate about coffee”

When Dulce Posadas talks about coffee, she smiles. Born into a coffee-farming family in Honduras, she was raised between the plantations on her family’s finca, appreciating from a young age the taste of a good cup of coffee.

Before she was born, her dad Wilfredo Posadas Alvarado arrived as a teacher in the region where their finca is now established. There, in La Unión, in the country’s western department of Copán, he fell in love with coffee, bought a tiny parcel of land and began to grow his own. What started off as a hobby became a lifelong dedication to coffee farming as a main occupation.

Since then, a lot has changed. “A long while back it was different,” he finds, observing that his coffee plants consistently need more fostering. New pests have appeared, the rainy and dry seasons have shifted, and the crops are feeble. Dulce describes how her family witnesses the effects of the changing climate around their finca. “We always have to wait for the rain.”

In 2018, Dulce was introduced to c&c and its initiatives. In one of its workshops, she first heard about the effects of climate change on the quality of coffee, and learned about new techniques and tools as well as the risks of diseases and chemicals. She began to urge her parents to integrate this knowledge into their daily life and work philosophy. “It was a process to change the mentality of the older generation,” she admits. But, finally, she managed to convince them.

Today, Dulce is proud of the climate-resilient coffee production at her family’s finca and hopes that they will be paid a fair price for sustainable coffee in the future. “We are all passionate about good coffee,” she says. “I hope it pays off.”